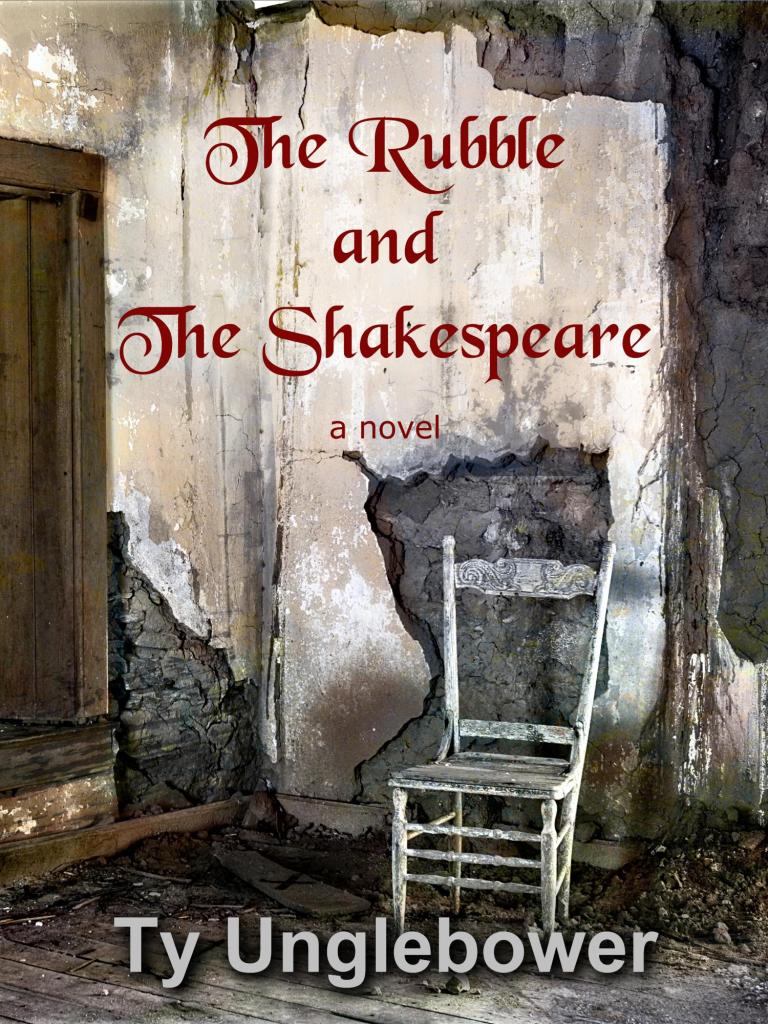

Book Launch!

Well, the day has arrived, friends. The Rubble and the Shakespeare is now live on all major e-retailers. I have entered it into my (admittedly) rudimentary My Books sections here on this website. It gets the job done, as it does for my other books, until something better comes along. Feel free to click on the title there to find your preferred e-store.

For today, I will say no more about the nature of the story, nor the nature of the process of writing it. That I have covered quite a bit over the last few months. And there will be more thoughts and sharing to come, as part of my promotional attempts. But for today the finished product is out there, waiting to be downloaded for $4.99. It joins the long line of books I’ve written and published, and the out-of-sync feeling of it being completed is no different for this volume than for any of the others. One day, it is done. One day it is for sale to the world. For my newest novel, that day is of course today.

My thanks for any support you may have already, or will give me as I offer this book to the world. The publishing and writing is over. The promotion and information aspect continue.

Similar Titles to The Rubble and the Shakespeare

A common, and perfectly logical way to promote a new novel such as my novel is to compare it to other works. What does it resemble? It’s an efficient if not foolproof way to suggest to readers the kind of book you’ve written.

As with any marketing strategy, I face a personal challenge when proceeding.

I tend to read fewer books in a year than is fashionable these days, due to my overall reading speed. As you can imagine, this means I have fewer reference points for comparison than those who devour books with the speed of a demi-god.

Not only that, I tend to choose my next read based not on how new a title is. I myself will pick up a book if it happens to be compared to one I’ve already enjoyed, but usually the choice is based on such things as word of mouth, happenstance, searching for novels about whatever I am fixated on a given day, or even just stalking the library shelves. When you choose titles in this way, you are just as likely to “discover” a book from 20 years ago.

My list of completed book spans decades and various genres. You may or may not have heard of many of the novels I’ve read and enjoyed.

Still, I’ll try to mention a few books I think accomplish similar things to The Rubble and the Shakespeare. In no particular order, here are four:

–Virgil Wander by Leif Enger. (2018)

This recentISH novel is, about a man who loses his memory and goes on to manage the movie house of a local failing midwestern town. Stacked with well drawn characters and free of the outlandish for most of its pages, this is a story about decent, diverse people getting to know one another under circumstances that are only slightly askew from the every day. A found-family vibe of community, with nods towards the power of imagination.

My upcoming novel is not quite as somber as this Enger work tends to be in places. Still, if you read and enjoyed this, I’m reasonably confident you’s also enjoy The Rubble and the Shakespeare.

–The Black Tower, Louis Bayard (2014).

This was the first of several Bayard books I’ve read, and thus far my favorite. This historical fiction and mystery/thriller is, I must point out, much more complex than The Rubble and the Shakespeare, because it is a different genre doing different things. However, much like Virgil Wander it is filled with what I found to be memorable characters that charm. This is particularly true of the protagonist of this first-person narrative. (My book is also first person this time around.)

I chose this one because like my novel, it maintains humor even in darker situations. Once more, the subject matter is more intense at times than I intend my story to be, but I hope the humor I’ve spread throughout is just as successful even if lighter in nature than that of Bayard.

–Legends and Lattes, Travis Baldree, (2022)

I will admit upfront that this is the outlier. This very recent and popular work is in the high-fantasy genre, complete with orcs and magic and trolls, etc.

The Rubble and the Shakespeare is quite removed from such things, for certain.

So why include it? Because the intentional selling point of this tale was its low stakes compared to its “high vibes.” A character-driven fantasy story free of quests and battles so common in the genre. That was the point. My novel has more stakes than Baldree’s. And the vibes are not fantastical. But like this 2022 bestseller, I’ve aimed to make atmosphere and characters the pillars of my story, allowing actions and conflicts to occur in their orbits as opposed to in their faces.

I’m sure there were other novels with a similar approach that were not as fanciful and would have made a better comparison, but I’m sticking to those novels I’ve actually read and enjoyed. Both this and Rubble embrace plot simplicity.

–A Whole Life, Robert Seethaler (2014)

Closer to a novella in length than a novel, I read a translation from the original German. This piece, despite being more literary than The Rubble and the Shakespeare aspires to be, was an easy read, and deeply atmospheric and personal. Introspective. It is the interior nature of this work combined with the mostly wintry, frigid environment (the mountains) that lands it on this list. Far fewer characters than my own first-person novel, and again, more somber in tone, I nevertheless recall certain similarities between Seethaler’s Andreas and my own Dimitri.

In case you missed the pattern, memorable characters saying and thinking thoughtful things are a thread that runs through the above novels, and, I hope, through my own. And while the purpose of this list was never to suggest I’ve written something superior to the work of these authors, I like to think that there is some noteworthy overlap in quality, theme, style, tone, or all of the above.

I hope you will download a copy yourself, priced at $4.99 once it is available five days from now.

The Rubble and the Shakespeare Almost Wasn’t

My upcoming novel, The Rubble and the Shakespeare will be officially released on the 27th of this month. I have spent more time writing, (and long periods not-writing) this novel than any of my previous works. I’ve gone into the reasons why in previous posts, but suffice to say I am excited to finally have it out there for purchase.

Yet despite taking so long, I nearly waited even longer to publish it. Despite how much of a drag on my mind that choice would have been, I pondered a delay because of the “rubble” part.

It’s difficult to recall now, but there was a time when neither the Ukraine nor Gaza were experiencing invasions, bombings, destruction, and so on. It was at such a time when I began writing this novel.

Then Ukraine happened. And more recently the Gaza mess started up. Needless to say, much of both areas now lie in literal rubble. This novel will come out in tensions across the world are hitting a peak over the Gaza bombings especially. Because I didn’t want to give the impression I was capitalizing on these events to sell a book, I wondered for a time if I should hold off on release.

I had decided to go ahead with it once, in wake of the Ukraine situation not long before Israel business of 2023 began, and I considered the topic all over again. Perhaps, I thought, I should at least change the title to not include the word “rubble”?

Book covers had been made, and marketing underway with that title, and I opted to leave it as is. A minor problem compared to those living the hells I have mention above, but nonetheless an issue for this author to consider.

It’s obvious by now that I chose to release the novel as scheduled.

The story involved a city rebuilding from a war, a revolution that ultimately overthrew a longstanding tyranny. The setting is now at peace, but still rebuilding. In the end, that is why I moved forward: rebuilding.

The story focuses on a Shakespeare play, the first in ages to be permitted in the country in question. On one hand, culture and art are their own reward in a time of rebuilding. Such is the position of Otto, the second most important character. Our protagonist, Dimitri, represents the other side to a degree…that maybe now is not the ideal time to explore flights of fancy such as the arts. He agrees to help Otto because of their friendship, not because of a devotion to culture.

Predicably, there are issues, plenty of them, in mounting a production in the middle of such an urban mess. Yet this is a story, if I have done my job, or what happens after the destruction is over. When we physically dig out of rubble and debris, do we not also have to dig our spirits out of confinement? Do we let some shit in the game squelch our attempts?

An individual must answer these questions for himself, but I I have told this story in order to present the questions to a set of characters. (You will of course have to read it to see how each of them responds!)

The point is, if I opted not to share this story now, in the midst of tragedy throughout the world, I would in a sense betray the very theme I hoped to establish in the first place: that there are times creativity and art still matter in the world to some of us, even if not to everyone.

And so both the title, and the release date for The Rubble and the Shakespeare remain unchanged. I hope you will read it, but even more than that, I hope that those in troubled places throughout the world will eventually get to the point where they to can ponder the arts and imagination once again…as they rebuild.

The Rubble and the Shakespeare: Extended Blurb

Over on my Facebook author page, (yes, I still use it, and would appreciate any new followers), I recently posted the official “blurb” for The Rubble and the Shakespeare. That is to say, the tight, concise, industry standard sub-120 summary without spoilers. Arguably the most important piece of marketing aside from the cover, it usually appears on the “jacket flap” of a hardback, or the back cover of paperbacks.

It is the “elevator pitch” of the publishing world.

And I hate it.

No, that’s actually too strong a sentiment. I don’t hate it. I wish it weren’t necessary, but it is what it is.

This, however, is my own website, where I am free to use some more words to describe the novel. Those that want a slightly more detailed overview of it, (still with no spoilers), this post is for you:

The setting is an unnamed country. I wanted the freedom to not set the story in a particular area, though it certainly borrows certain aspects from other real-life nations and regions.

Timeframe: consistent with the mid 1990’s, though no year is given.

This country spent most of the previous century under a tyrannical government, referred to as “The Regime.” As the novel opens, a successful revolution a few years previous ousted the Regime and installed an elected government. Overall things have improved, but the rebuilding of cities other than the capitol city has been slow, starting with downtowns and working its way to the outer neighborhoods.

The story takes place in one of these outer parts of the city, where major signs of the war remain, even as people try to live their lives. Hence the “rubble” aspect of the title. There’s a lot of it where our story takes place.

Dimitri is the protagonist. In his 40’s now, and a curmudgeon in the making. He, like many, was evacuated from his home during the initial conflict, and moved to other, safer parts of the city, where the free government had seized control and taken over buildings for refugees. Dimitri now lives in what was once a hotel, on a modest government pension for survivors, as do most of his friends and acquaintances.

He walks with a limp due to a bad knee he injured during the conflict, and has difficulty moving around quickly, or getting one of the few public jobs that are trickling into the area.

The Regime forced him to be a building safety inspector due to his talent for math and science in school, but there is no longer a place for him in that field under the elected government.

So, like many refugees in their own city, Dimitri survives. Gets by. Looks for work when he can, but otherwise has few options.

The story begins when his longtime friend Otto comes to him with a box of books that would have been banned under the Regime. Copies of The Tempest by William Shakespeare. Otto, it seems, is going to try to stage this play, possibly the first Shakespeare in generations in that part of the world. But he needs Dimitri’s help, mainly in finding a safe structure to perform in.

The cynical-but-well-meaning Dimitri agrees to help due to how fond he is of Otto, though privately wonders if there isn’t something better Otto and others could be doing with their time. At Otto’s insistence he reads The Tempest; he finds himself confused more often than inspired by the text, though he tries to understand.

Problem after problem and obstacle after obstacle pile up around the production like the debris around the city, and Dimitri’s initial single day of help turns to days, and then to weeks.

Derelict buildings. Eccentric and unreliable actors. A public unused to theatre of any kind. A whole host of potential issues that have yet to even reveal themselves. Dimitri would do just about anything for Otto, but does it make sense to put up with such struggles for a long-banned and forgotten play in a city still half in ruins?

The Rubble and the Shakespeare will be available as an ebook starting November 27, 2023.

The Central Question of The Rubble and the Shakespeare

What’s the single question at the heart of my upcoming novel The Rubble and the Shakespeare?

Stories often have multiple underlying questions, or themes. My novel is no exception, but one question is central—central in that not only does the novel itself and its characters consider it, but as the author so do I. The question:

Are creative endeavors justified in the midst of struggles?

I’ve pondered this question at numerous times in my life long before this novel came about. Yet between some personal issues, as well as the Pandemic dominating much of my thought and time during the process of writing The Rubble and the Shakespeare, this felt especially topical.

The experience of writing this novel paralleled the plot of same. This wasn’t my intention. In fact this wasn’t the novel I started; just before the pandemic planned on an entirely unrelated story. This was slow going, and ultimately it was clear to me that it was not the time to pursue that novel, so I iced it.

The decision to put the first few thousands words in a drawer, (only the second time in my career I had ever done that) acted as a millstone, acting as strong inertia against writing anything at all, including this novel.

That inertia reared its head more and more as local implications for the worldwide COVID situation became clear. Libraries closed. Non-essential people encouraged to not leave the house except for vital supplies. Some of my family members contracted the virus early on before there was even a hint of a vaccine or treatment for it.

These circumstances decreased my writing productivity.

Perhaps such mental and emotional fatigue were understandable, given the whole world suffered from it and still does. Yet beyond lacking the literal motivation to write, I began to ponder, really for the first time in my life, if the process itself had value during such a time or worldwide struggle, and personal depression.

Not only did writing and pondering a novel require twice as much energy than normal, I remained encumbered by endemic low readership of any of my work. (A side effect of my lackluster marketing skills and resources since my first book.)

Writing in a world on its feet, but with few readers was one thing. Writing for loyal readers, happy for the distraction when the world was on its knees would have also been one thing. In both scenarios I could locate the motivation, I think.

Committing to the laborious task of writing and marketing a novel unlikely to be read by many people while the world was brought to its knees? At best it seemed naïve, and at worst delusional.

What is the point?

I wrote only sentences every month or two at home for much of the first year and a half of the COVID crisis. Only once libraries cautiously opened again, and I forced myself to visit mine almost daily in 2022 did the ball at last roll on this novel.

You’d think completing and publishing it would have finally justified the dedication.

It didn’t. Not on its own. I struggle with it even now, and perhaps will do so henceforth, even once the pandemic is merely a history book chapter.

Still, this question, this struggle to determine the “worthiness” of creativity, or the arts as a whole informed my writing of The Rubble and the Shakespeare.

The characters, refugees in their own war torn city obviously have different issues to deal with than I did and do. Yet the question is the same. “Is it worth it? Does this still matter, given all the other crap that’s going on around us?”

I hope you’ll download a copy on the 27th to find out if they answer the question any better than I have.