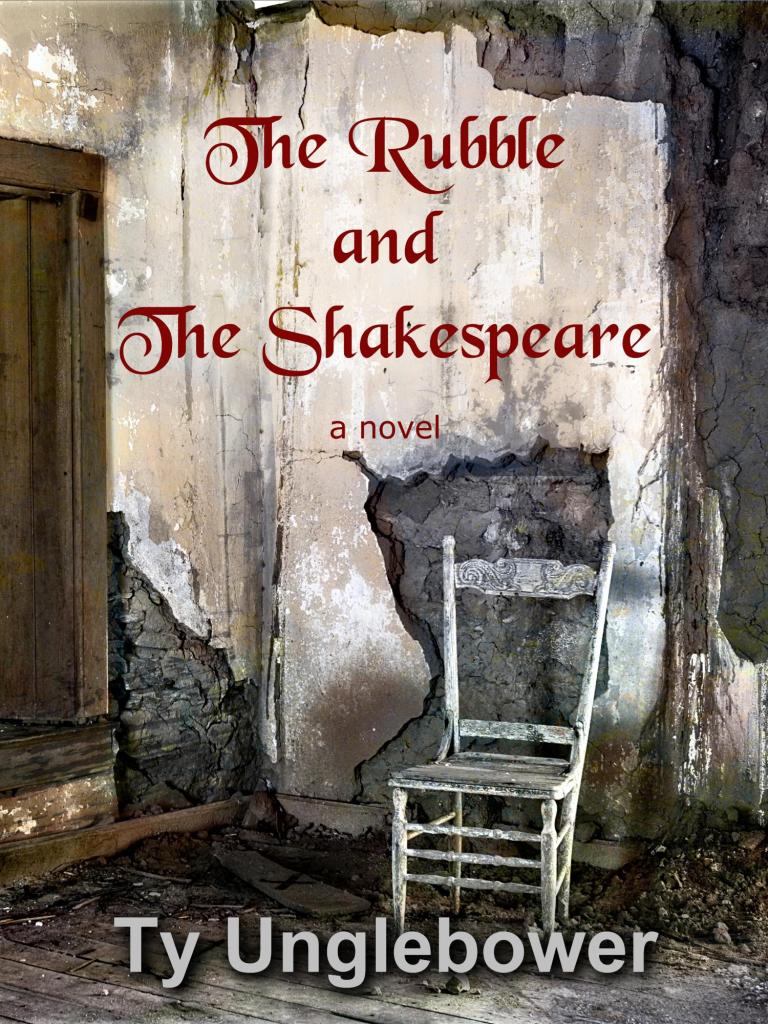

The Rubble and the Shakespeare: Extended Blurb

Over on my Facebook author page, (yes, I still use it, and would appreciate any new followers), I recently posted the official “blurb” for The Rubble and the Shakespeare. That is to say, the tight, concise, industry standard sub-120 summary without spoilers. Arguably the most important piece of marketing aside from the cover, it usually appears on the “jacket flap” of a hardback, or the back cover of paperbacks.

It is the “elevator pitch” of the publishing world.

And I hate it.

No, that’s actually too strong a sentiment. I don’t hate it. I wish it weren’t necessary, but it is what it is.

This, however, is my own website, where I am free to use some more words to describe the novel. Those that want a slightly more detailed overview of it, (still with no spoilers), this post is for you:

The setting is an unnamed country. I wanted the freedom to not set the story in a particular area, though it certainly borrows certain aspects from other real-life nations and regions.

Timeframe: consistent with the mid 1990’s, though no year is given.

This country spent most of the previous century under a tyrannical government, referred to as “The Regime.” As the novel opens, a successful revolution a few years previous ousted the Regime and installed an elected government. Overall things have improved, but the rebuilding of cities other than the capitol city has been slow, starting with downtowns and working its way to the outer neighborhoods.

The story takes place in one of these outer parts of the city, where major signs of the war remain, even as people try to live their lives. Hence the “rubble” aspect of the title. There’s a lot of it where our story takes place.

Dimitri is the protagonist. In his 40’s now, and a curmudgeon in the making. He, like many, was evacuated from his home during the initial conflict, and moved to other, safer parts of the city, where the free government had seized control and taken over buildings for refugees. Dimitri now lives in what was once a hotel, on a modest government pension for survivors, as do most of his friends and acquaintances.

He walks with a limp due to a bad knee he injured during the conflict, and has difficulty moving around quickly, or getting one of the few public jobs that are trickling into the area.

The Regime forced him to be a building safety inspector due to his talent for math and science in school, but there is no longer a place for him in that field under the elected government.

So, like many refugees in their own city, Dimitri survives. Gets by. Looks for work when he can, but otherwise has few options.

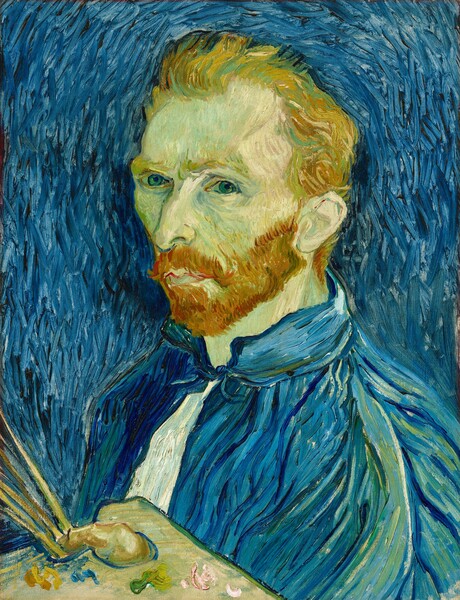

The story begins when his longtime friend Otto comes to him with a box of books that would have been banned under the Regime. Copies of The Tempest by William Shakespeare. Otto, it seems, is going to try to stage this play, possibly the first Shakespeare in generations in that part of the world. But he needs Dimitri’s help, mainly in finding a safe structure to perform in.

The cynical-but-well-meaning Dimitri agrees to help due to how fond he is of Otto, though privately wonders if there isn’t something better Otto and others could be doing with their time. At Otto’s insistence he reads The Tempest; he finds himself confused more often than inspired by the text, though he tries to understand.

Problem after problem and obstacle after obstacle pile up around the production like the debris around the city, and Dimitri’s initial single day of help turns to days, and then to weeks.

Derelict buildings. Eccentric and unreliable actors. A public unused to theatre of any kind. A whole host of potential issues that have yet to even reveal themselves. Dimitri would do just about anything for Otto, but does it make sense to put up with such struggles for a long-banned and forgotten play in a city still half in ruins?

The Rubble and the Shakespeare will be available as an ebook starting November 27, 2023.

The Central Question of The Rubble and the Shakespeare

What’s the single question at the heart of my upcoming novel The Rubble and the Shakespeare?

Stories often have multiple underlying questions, or themes. My novel is no exception, but one question is central—central in that not only does the novel itself and its characters consider it, but as the author so do I. The question:

Are creative endeavors justified in the midst of struggles?

I’ve pondered this question at numerous times in my life long before this novel came about. Yet between some personal issues, as well as the Pandemic dominating much of my thought and time during the process of writing The Rubble and the Shakespeare, this felt especially topical.

The experience of writing this novel paralleled the plot of same. This wasn’t my intention. In fact this wasn’t the novel I started; just before the pandemic planned on an entirely unrelated story. This was slow going, and ultimately it was clear to me that it was not the time to pursue that novel, so I iced it.

The decision to put the first few thousands words in a drawer, (only the second time in my career I had ever done that) acted as a millstone, acting as strong inertia against writing anything at all, including this novel.

That inertia reared its head more and more as local implications for the worldwide COVID situation became clear. Libraries closed. Non-essential people encouraged to not leave the house except for vital supplies. Some of my family members contracted the virus early on before there was even a hint of a vaccine or treatment for it.

These circumstances decreased my writing productivity.

Perhaps such mental and emotional fatigue were understandable, given the whole world suffered from it and still does. Yet beyond lacking the literal motivation to write, I began to ponder, really for the first time in my life, if the process itself had value during such a time or worldwide struggle, and personal depression.

Not only did writing and pondering a novel require twice as much energy than normal, I remained encumbered by endemic low readership of any of my work. (A side effect of my lackluster marketing skills and resources since my first book.)

Writing in a world on its feet, but with few readers was one thing. Writing for loyal readers, happy for the distraction when the world was on its knees would have also been one thing. In both scenarios I could locate the motivation, I think.

Committing to the laborious task of writing and marketing a novel unlikely to be read by many people while the world was brought to its knees? At best it seemed naïve, and at worst delusional.

What is the point?

I wrote only sentences every month or two at home for much of the first year and a half of the COVID crisis. Only once libraries cautiously opened again, and I forced myself to visit mine almost daily in 2022 did the ball at last roll on this novel.

You’d think completing and publishing it would have finally justified the dedication.

It didn’t. Not on its own. I struggle with it even now, and perhaps will do so henceforth, even once the pandemic is merely a history book chapter.

Still, this question, this struggle to determine the “worthiness” of creativity, or the arts as a whole informed my writing of The Rubble and the Shakespeare.

The characters, refugees in their own war torn city obviously have different issues to deal with than I did and do. Yet the question is the same. “Is it worth it? Does this still matter, given all the other crap that’s going on around us?”

I hope you’ll download a copy on the 27th to find out if they answer the question any better than I have.

The Autistic Writer: A Wrap Up

All throughout this year I’ve posted about the perspectives of a writer that is also Autistic.

Several take aways present themselves for those who have read more than a few of these posts. Mostly certainly, the fact that Autism manifests itself differently for each person on the Spectrum. I may struggle at something another person with ASD may excel at.

On the other side of this same coin, I’ve talked about trends in Autism that are about as near to universal to the experience as one can hope to pinpoint. Among such are an interior life, and inward-oriented mindset.

Also among the most common truths about Autism is the alternate take on the social structure and behaviors of society at large. (Which in and of itself presents differently depending on the society a given Autistic grows up and lives in.)

Yet as I bring this series of columns to a close this week, I’ll remind the reader that even when I am not opining specifically on the nature of being a writer with ASD, everything that i write contains a component of being Autistic. No matter how much I may mask, on purpose or subconsciously, no matter how much those out there may choose to “overlook” my Autism, or in darker cases dismiss it, no matter if a readership knows, or still somehow is unaware of my place on the Spectrum, every word I put down passes through that filter. This series has merely tried to illuminate this truth with greater details than may be generally understood.

Autism Spectrum Disorder is not something to be conquered, or worked around, and certainly not ignored or masked. It is simply a component of what and who I am. It has always been so, even before I knew I had it. In these weekly posts this year, I hope, if nothing else I have presented this truth more than all others.

My whiteness will never allow me to know racial oppression. My cis-hetero nature precludes me from fully comprehending with queer identity issues, and of course I am a male, unaware of the nature of being female. Autism is nonetheless a minority status that, if left unspoken of can lead to it being (remaining?) unaccepted. Which in turn opens the door for misunderstanding at best, oppression at worst.

The world tends to frown upon the outlier, the exception, the skewed and the alternative. Only knowledge and exposure can change this, and such an outcome is possible only if I am open about what makes me who I am, when I do what it is I do. More than anything else, that’s what these columns have been about each week.

And yet, the Autistic is still only half of what I have explored. “Writer” is of course the other primary aspect of these weekly explorations. I wonder if at times if I am anymore able to divest myself of being a writer than I am able to divest myself from being Autistic.

Unlike being Autistic, I do no have to be writing. I could close this laptop and never write another word, but would remain Autistic.

Autistic, but perhaps not authentic.

Writing is difficult. Laborious. Time consuming and energy draining. It’s an activity that never quite mirrors the speed or the coloring of what one sees in ones head, and yet is perhaps the best remedy for placing what is in one’s head in a position to be partaken of by others. Unlike some writers, I don’t break out in a cold sweat chomping at the bit to just throw myself in front of this train daily. But if I were to never do it again, even to myself, I have to wonder if I’d be betraying something of me even more mysterious than Autism and all of its horrors/wonders.

Then again, if not for the one, would there be the others. Plenty of other writers are not Autistic. Plenty of people on the Spectrum are not writers. Did I call myself a writer because of the effects of ASD?

In order to truly answer that question in good faith, I would have to separate the two. Of course, my dear reader, that is not possible. For I am both Autistic and a writer by nature, if not always by presentation.

Here at the end of this series, though, that is of course the point of it all: I am the Autistic Writer.

The Autistic Writer: Self-Publishing

I’ve spoken of my self-publishing journey before on this blog. If you follow me on other social media platforms, you’ve heard me talk of that adventure as well, and how it relates to my Autism. But as this weekly series draws to a close soon, I wanted to share my approach to something integral to my author career.

I have self published four novels so far, and 6 other books of various type. For those who may not know the lingo, this means that certain websites, (usually Draft2Digital for me), electronically receive my final draft of a book, well-edited and proofread to the Nth degree. The system in question formats the manuscript for ebook, creates the needed files, attached my cover art, and places my book and it’s descriptors (meta data) on the various ebook retailers of my choosing for you and hopefully many others to purchase and download to your respective device.

After I have done my darndest to market the crap out of it.

This, as opposed to what they now call “traditional publishing.” In such, one must still have the best possible final draft. One shops the idea around to many of what is called a “literary agent.” If interested, this agent will ask for a sample of your book. If the agent takes you on, it becomes their job to then convince publishing companies to accept your book because it will make money.

Some changes are made depending. You may and probably will be asked to rewrite the book a few more times. The press in questions puts your book onto paper and into bookstores. (Where self-published books rarely get accepted.) Hopefully people in book stores buy it.

After I (that is to say NOT the publishing company in most cases) once again market the crap out of it.

The whole process, on the whole from final draft to available to purchase in stores takes 3-5 years on average. If you get an agent. It could also sometimes take several years to get an agent in the first place, who could in turn take many more years to find a publisher if they do at all.

It’s a wonderful rewarded process for those less interested in control of their work, and with the patience of a saint.

Unfortunately, neither trait applies to me.

As an Autistic person, I am very much uncomfortable with giving up so much control, and pace as the traditional publishing route requires. I thrive on routine and predictability of task. Adaptability of schedule if needed, as well as the freedom to change my mind. (My upcoming novel is not the novel I had planned to publish yet, originally. More on that in future posts.)

I may or may not succeed at marketing, and may or may not sell many copies. Usually I do not. But the process is 98% mine. Sink or float it will do so, by and large while at liberty to pursue my own rhythms and abilities.

Traditional publishing requires perhaps a score of people doing their job, doing it well, and doing it for many, many other people, making me, the author, a lower priority, (Another Autistic ick of mine…being someone’s low priority.)

And when all is said and done, I can look at the finished product knowing I did it all. (Or sometimes help with cover art, as I have this time around, again more on it later.)

I feel “in contact” with my books from word one to final placement in stores when I self-publish, even if I don’t generally have a book store presence. That tangible proximity couples well with my overall sense of creative vulnerability that turns up at times.

For my own money, I would advise other folks on the Spectrum to try self-publishing. Of course everyone is different, as I say all the time. But going by trends, best guesses, and my own personal experience with both being Autistic, and being a writer, (what’s the name of this series again??) I feel most Autistic authors are more likely to find more satisfaction more often with the self-publishing route.

Will I swear I will never seek an agent? No. I will never swear to it. I can’t see it occurring in a definable future, but the time could come when I choose the “traditional” route. Teamwork with publishers and agents may appeal to a different aspect of my Autism, after all. But because I am not much of a gambler, I like to keep dice roles to a minimum, and there are far too many dice flying around in traditional publishing success right now for me to consider it.

Note: Next week will mark the conclusion of this near-year long column about being both Autistic and a writer, so that I can concentrate more on the final push and additional discussion for my upcoming novel, due in November, The Rubble and the Shakespeare. —Ty

The Autistic Writer: Rejection

Rejection. It takes on several forms and I hate all of them. Most writers hate all of them. Hell, most people hate all of them.

Being Autistic nonetheless adds a dimension to the experience of rejection, as it does to so many other common components of daily life.

It’s called Rejection Sensitive Dysphoria, and unlike my Autism I have not received an official diagnosis. It is however quite common for those on the Spectrum, and after years of consideration, I’m willing to self-diagnose in this case.

RSD is defined as experiencing overwhelming levels of emotional pain in response to rejection or perceived rejection, to the point that it interferes with one’s ability to regulate one’s emotions in wake of rejection and failure. (Thank you, ClevelandClinic.com.)

As with Autism itself, RSD is on a spectrum. I experience some aspects of it, and not others. Over time, I have learned to better regulate my responses, and no longer present in the same ways I may have, say, in high school.

But it’s there.

When people choose not to read my writing, it is a rejection. On the surface it is merely a choice to not engage with me and/or my creations, not a judgement of my worthiness as a human being.

But it is still a rejection.

This choice is particularly painful when friends and comrades opt not to read my books on a regular basis. (Or in some cases, opt never to come see me perform on stage.) Most of them are not rejecting me as a whole person, but I can feel it as though they are doing so, and I need time to recover.

This is because:

- I work hard on my writing, and put a lot of myself into it. I advertise and share updates of same far and wide within my circle, and the numbers of engagement among them remain low. To put so much of me into something that others who have also been a large part of my life opt not to look into feels for all the world like a disinterest in me.

- My writing, (sometimes acting) are two of the few ways in which I can present myself to the world free of Autism-related difficulty. Any chance I have of making even the slightest impression on my community, or on individuals has upwards of 90% chance of being connected to one of these two crafts, because of how ineffective I am at connecting with people otherwise. When my writing goes unread by the community at large, (and it usually does), that is another form of rejection. I am, at least in the moment, denied my rare chance to impact the world, and the people in it.

Combine this with the (likely) presence of RSD, and you can see why I must struggle at times to maintain enough motivation to continue the labor, (and much of it is labor) of writing.

As I mentioned already, I am better at dealing with all of this than I was once. One by one, as different aspects of my world presented me with rejection after rejection through life, I came to an emotional place of tolerance for it, even if not total acceptance. A certain peace, if you will.

Yet when it comes to my writing? Tolerance of rejection has been slower, and requiring more emotional taxation than much of the other facets of my existence.

There is a saying that the only thing a true writer must learn to do all the time, besides write, is be rejected. I’m aware of this truth. With time, I may be able to embrace the process and the process only of writing as opposed to the levels of my readership. (Ironically the sage advice of many successful authors.) Still, if I had to guess, if ever I get over it, it will be the final type of everyday rejection I will make peace with.