The Autistic Writer: Music (Not) To My Ears

I’ve noticed a common perception out there that music and writing almost always go hand and hand. Interviews with authors, author forums and other such platforms usually come round to the question of what soundtrack any given writer plays while working.

Don’t ask me to cite a study on this, but it seems the more fanciful the material, the more interest there is, (and the more assumptions made) about the author’s taste in background music. In my experience, the general non-writing public tends to assume a fantasy writer immerses themselves in bombastic classical or meandering New Age compositions.

Yet even more “down to earth” fiction lends itself to certain stereotypes when it comes to the writer’s soundscape. Many think of thriller writers pounding away at the keyboard to the sounds of upbeat, high percussion pieces, or romance authors carried away be string rhapsodies as they weave their tales of love.

For all I know, all of these are true more often than not. Speaking only for myself, I can say I almost never have music on as I work.

It happens. It’s just that it doesn’t have to happen. Furthermore, it’s counterproductive more often than helpful.

My theory is that music and writing, despite being cousins of a sort in the creative arts actually “live” in two different parts of my Autistic brain. Though writing obviously requires a strong imagination and willingness to explore same, in the end writing a story becomes an external event. The words I form go onto the screen or onto paper, in order to grant the rest of the world access to same. An obvious expression of interior thoughts and feelings, but not a permanent resident of my mind exclusively.

From an early age music, of all varieties, has pulled me inward further. I consume music, as opposed to actively creating it as I do writing. Someone else has done the work for music, and I am often carried by it deeper into myself. I may encounter an idea that becomes part of my writing in such a state, but the act of writing becomes difficult there. The images I am creating conflict with the images, feelings and emotions of the song that wrap around me.

This may not be as intense as it was when I was younger, but still very much the case.

Even the times I have sought out a specific type of music to aid me in writing a particular scene or story, the results have been mixed. The proverbial stars must align just so for music to enhance as opposed to hinder my writing.

Pure silence would be problematic in its own way; I like there to be some aspect of ambient noise. Yet given the choice, I fall closer to the “no noise” end than I do the “playing music” end of things when it comes to work.

Not a weakness. I have no regrets. I just have a far less interesting answer to the common question of “what do you listen to when you write?”

The Autistic Writer: Work Spaces

I published a book a few years ago called 14 Fantastic Frederick County Writing Spots. In that free non-fiction guide, as you can probably guess, I highlighted and described 14 different, non-traditional places in my home county in Maryland where one could work on one’s writing.

While I don’t visit each of these myself on a regular basis, I have done writing at some point in all of them, and will certainly do so again.

That’s because I tend to need time away from home in order to accomplish a certain amount of writing over time.

I thrive on routine, as an Autistic adult. Yet on the opposite side of that coin is at time a potent restlessness that renders work, particularly writing work more laborious.

For lack of a term, I can “disappear into myself” more at home that away from home. This doesn’t always mean that I sit in a dark room saying and doing nothing. (Though that happens too.) But home is almost too safe, if you will, to write certain things for certain amounts of time.

Reject the notion that we must be constantly uncomfortable in order to create. Yet even the most imaginative person ever needs to muster at least some external mental energy, if they ever expect anyone else to enjoy what they do.

In other words, the words won’t write themselves.

I will never deny the possibility that a rich inner world, present in myself and many other Autistic people is useful, perhaps a gift for the arts-oriented person, but thankfully nobody else can enter my mind and see what I have come up with. I have to write it out.

The very act of not being at home requires me to avoid that potential full immersion into my own consciousness. That extra slice of alertness to my surroundings allows for a mindset just conducive enough to compose the words on a regular basis.

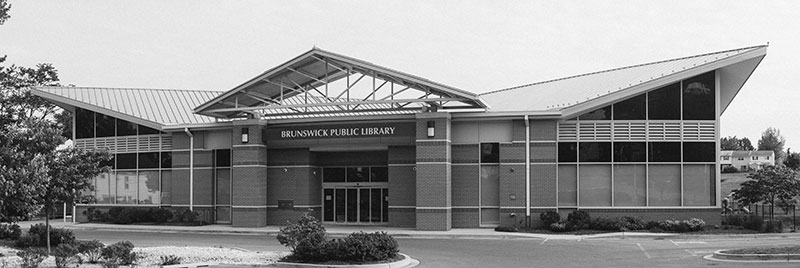

Take my upcoming novel, The Rubble and the Shakespeare for example. Earlier on I had gone months being unable to summon the proper mental state to write more than a sentence or two at a time, if that. Only once I determined to take my laptop to the local branch library every day did I break free from that slump enough to finish the first draft by the fall of 2022.

I have a preferred table at that library, and I tend to go there within the same two hour range even without thinking of it each visit. Obviously, preference for routine will never abandon this ASD mind of mine. Much of my writing, lifetime, has still happened at home.

Nevertheless at times even I can distract me, and putting on just that thinnest of masks out in public makes me more productive.

(Even if, ironically, I write this post sitting in my bedroom.)

The Autistic Writer: Writer Retreats

Writer’s retreats. Some swear by them. They can range anywhere from a few hours at a local state park with a brown bag lunch and a writers group, to several weeks in idyllic or even exotic locations, with meals provided.

Needless to say, unless you’ve won a contest, the more a retreat provides the higher the price.

Like most writers, for the time being the cost of most such experiences is prohibitive.

Yet if money were no object, the prospect of a retreat would still give me pause. There’s much to consider for an Autistic mind before embarking on such an adventure.

Obviously, there is the social aspect. People with Autism are not de facto anti-social. (Some are, just as with anybody else.) Yet their ability to read social cues, to fully understand the nature and purpose of a social interaction is skewed from the norm in most cases. Couple this with a not-uncommon propensity for sensory overload and an Autistic writer may get less done on a retreat than they do at home. (Which is often the “safest” space for them.)

I would argue the biggest concern is the accommodations. Sleep, or bedtime if one sleeps little, is a key time for an Autistic person. I venture to say a roommate of any kind but particularly a stranger would be a deal breaker for most of us. Even if only for a few days, this is a vulnerability that would detract from everything else; I would almost certainly not attend a retreat that required rooming with someone.

These concerns don’t stop at bedrooms, however. How much socializing with other attendees is expected? Are there seminars at the retreat? Are they required or optional? Is there any limit to how large these are? What may be just a description of the experience for some could make or break the entire affair for someone with Autism. I myself would want to keep any expected discussion to a minimum at any retreat I attended, though I personally could handle one or two.

How about meals? Many people on the Spectrum have what are called “safe foods,” or meals they can eat over and over, particularly when other aspects of their day are unpredictable. Can attendees bring their own food? Are any of these safe foods on the menu of the retreat?

Are meals communal? Plenty of retreats I’ve looked into require attendees to come together for meals. Nightmare of nightmares some requires participants to help prepare same. The horror!

A handful of the higher end retreats bring at least a lunch to the writer’s door so as not to disturb them. I cannot squeeze blood from a stone, but this option would be worth me scrounging for money to afford said luxury, all things being equal.

Can one visit the campus before signing up? The newness of the surroundings would in most cases not bother me if they were otherwise acceptable. But plenty of people with ASD would appreciate or even need to familiarize themselves with the environment before ever making the decision to attend. Does the retreat in question allow this?

I myself want to be at least within hollering distance of others, as opposed to alone on a mountain road, despite my often-solitary nature. This is in case I become flustered or disoriented in the event of an emergency. One of my fears no doubt connected to my Autistic wiring.

Urban vs rural. Large population vs. small. Seasons. Organizing institution. Distance from home. All or some of these things, along with plenty more, will determine the usefulness and pleasure of a writers retreat to an Autistic writer.

Make no mistake, however. The ideal of a retreat for writers is not at all threatening to the Autistic mind. In fact, once all of the above-mentioned aspects are taken into consideration, the basic ideal of a retreat may be just what an Autistic is looking for.

The quiet. The (at least part time) isolation. The guaranteed lack of distraction. “Permission,” to hand everything over to our creative side. A schedule, if only for a few days, that we can consume entirely with imagination. A retreat with just the right balance of components may just be a temporary utopia for a person’s Autism as well as their writing process.

And despite what I’ve already mentioned here, don’t discount the social aspects of a retreat. So long as interacting with others is 100% voluntary and not a requirement in the offered package, a writers retreat might help us rid ourselves of the dreaded small talk. Everyone there, after all is a writer, working on a project. This means a built in special-interest for a time. You always know at least one topic everyone is willing to discuss with you. Under those conditions even I could see myself talking to strangers.

A little bit. If I meet my word count for the day. And if I can eat alone. Without a roommate. And they have the food I want.

So yes. My ASD will affect my choice of retreat as much if not more than the price. But it won’t keep me away.

Maybe someday, when I sell enough copies of everything.

Next week I’ll explore the related but distinct topic of writer residencies.

The Autistic Writer: Handwriting

Aesthetics are a lesser mentioned aspect of being on the Spectrum. Whether it be an avoidance of certain clothing due to a repulsion to a color/material or spending hours of labor and hundreds of dollars on displaying collections, Autistic people often make use of aesthetics and milieu to make their segment of the world more comfortable for them.

Hyperfixations and “special interests” are active components in this as well as comfort. So much so that sometimes we on the Spectrum sacrifice a bit of comfort for the sake of the presentation.

Comfort will in most cases win out eventually. But if one is stubborn, (as I am about some things), it could take quite some time.

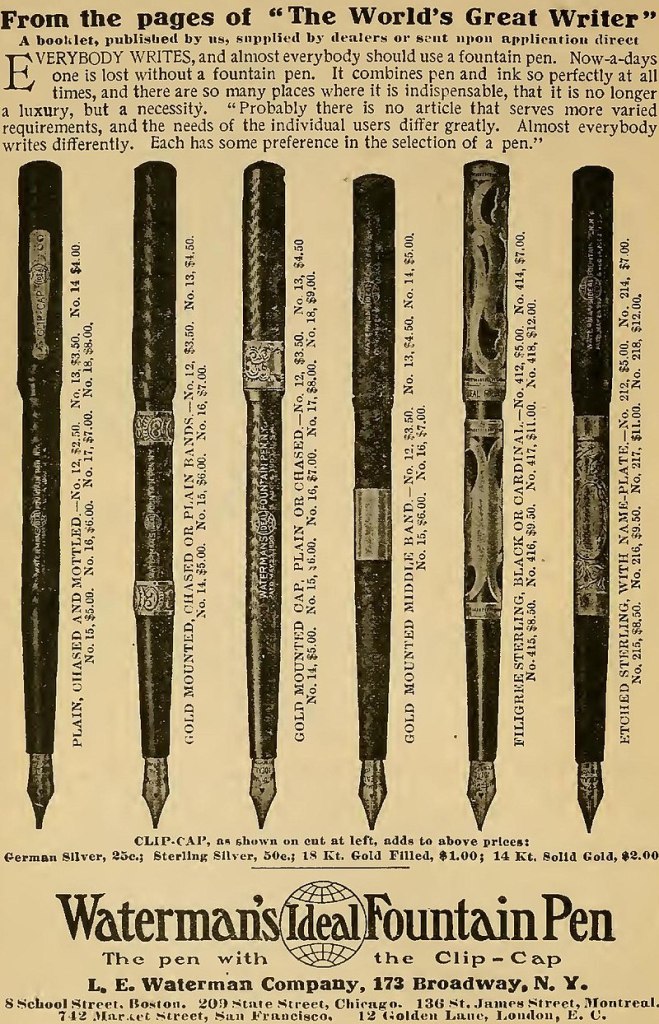

I have a bit of a fixation on paper and ink, writing and drawing.

This doesn’t sound surprising. I’m a writer after all. These elements fit right in to that. In fact, aren’t they required?

Well, no.

The truth is, I can barely write with my hands.

My difficulty with handwriting goes back as far as my ability to read words. Not only has my printing always been bad, and my cursive worse, the physical act of writing is uncomfortable to me, bordering on painful depending on circumstances.

We’ve never known exactly why. Words such as “disgraphia” have been mentioned, but no diagnosis has been made in that regard. All I know is that I can write uninterrupted by hand for three fourths of a page on a good day before the pain and or numbness in my hand sets in. Undeterred it can radiate as far as my upper arm and even parts of my shoulder.

From 8th grade until only a few years ago, I wrote nothing in cursive but my signature. A combination of the aforementioned pain, and the fact that at best it was 50% legible if I moved at anything approaching a productive pace meant that I gave it up.

Even when writing slowly, I often lost the memory of how to form certain letter combinations.

What I started journaling, I opted to use cursive again on a regular basis. The same with my “writer ideas” notebook that I take with my most places. It’s an expensive item, and printing feels unworthy of it’s quality.

I want to be the person that literally writes many things, instead of typing them. At least at first. It’s that fixation on the aesthetic of ink scratched onto blank pages and forming thoughts.

But despite years of attempting to make this a regular practice, nothing has eased the quick pain during the process, and the frequent illegibility of the result. Grips, accessories, page angles, ink types, pen types, hand positions, very low speed movements: it doesn’t matter. The handicap, whatever it’s nature, remains.

Meaning that writing of any length, or required speed requires typing.

As I said, I am at times obstinate about it. I still in the back of my mind pretend I am just an idea away from pain free handwriting. Intellectually, however, I know damn well it will never happen.

Only in the last year, well into my attempted, bullheaded attempt at a handwriting renaissance have I begun to switch away from cursive, and back into printing in notebooks, (and for poetry…never type poetry.) Even printing requires concentration and frequent breaks during which I shake out my hand like a damp rag. But at least I can usually read the words before me, and reference them as needed. (You know, the entire point of writing something down?)

I have much to say, and like everyone have only so many hours and days in which to say it. To come even into the same solar system of saying all of it, I must type more, not less, as time goes on. This would be true even if I myself am the only audience. It’s just plain silly to deceive myself on this issue. Writing out poems, quick thoughts into a notebook, and going by hand in a nice journal are as far as it will ever go.

Yet when I visualize my very identity as a writer, I don’t see this laptop, despite 90% of everything I have ever done being types. I see pages, and ink wells, pens and bindings and even the occasional quill and parchment for kicks.

Much like my sensory-based hatred of tight clothing on my skin, this neurotic obsession, cousin to my Autism shall remain, even in the face of evidence for better results from other approaches.

At least there is always my signature.

The Autistic Writer: Coming of Age

Last week I mentioned how stories of bullying don’t appeal to me in fiction, as both a writer and a reader. In quick review, it hits too close to home for me to find any redeeming qualities in such story arcs.

Today I want to talk about another common narrative theme in fiction that I dislike just as strongly. Only in this case, it’s for what amounts to the opposite reason.

I’m talking about so called “coming of age” stories.

If a movie or book is described as such, it’s already lost me. Not spending the time.

Why? Not because it hits too close to home, but because it is too foreign, not relatable at all to me.

I have of course been on the Autism Spectrum my entire life. Yet this wasn’t discovered until well into my adulthood. So imagine not only going through the difficulties of growing up Autistic, but not having enough knowledge to label very specific problems for what they were. I knew only I was weird in such a way as to repel and repulse most people my own age.

Even erstwhile friends kept a certain distance to point.

One of course gets older, more mature perhaps, but in a vacuum of social isolation I endured for most of my lonesome childhood, one is never anointed with the sacred oils of a “coming-of-age” story.

Being seven when my father died, and having no other family males step into my life to be even a partial male role model for this often “feminine” boy certainly put a hell of a damper on a more typical coming of age experience. Yes, I would have rejected much of what could have been offered, but knowing it was there would have provided at least some rungs on archetypical ladder to what was once called “manhood.”

Let’s be frank about the topic, though. Though any number of turning points in a child/teen’s life can be the focus of a coming of age tale, what little I have read/watched almost exclusively involves the rapturous loss of virginity. Short of that, it centers around a first kiss or first love situation.

Sex has never been a driving force in my life, even when it is supposedly “everyone’s” driving force. It becomes exhausting in 7th or 8th grade to pretend you enjoy talking about someone’s “tits bouncing” during track practice for the 4th time during that lunch period, so you just stay quiet and let other people talk.

Which means, of course, you are labeled gay. On top of everything else you’ve already been labeled, that is.

To this day as I write this, I am not at all certain that the 9th grade subterfuge to get me to go out or at least flirt with a girl that supposedly expressed her attraction to me in secret was legitimate or an attempted humiliation. Autism means I wasn’t perspective enough to know, and I wasn’t desperately horny enough to barrel into anything without more information.

“Lack of information” was also the reason I talked myself out of crushes and interest in girls at a young age. Yes, fear of being rejected acted as ballast at times, it does for everyone. Yet if I couldn’t explain why a girl was more interesting than the others to me for a while, I dismissed it.

This is not riveting, or even moving plot fuel for novels.

My first kiss was my first kiss. It occurred, I appreciated it, it concluded. I describe my first sexual experience in the exact same way. Neither were, and have not in retrospect become pivotal moments of my existence. If I’m honest with you, I don’t even recall all of the exact details of either event, anymore than I can recall the exact details of the very first time I ever rode a bike or shook somebody’s hand.

And I was supposedly more of a man after these moments than I was before?

If I, a writer, am that ambivalent about the moments of my life that were literally my own “coming of age” story, how am I to ever come up with thoughtful fiction about a character’s “awakening”?

I could of course, read and watch more of those stories, and study them. Get an idea, as I so often have in life, how the rest of the world feels things I have never felt in order to write fiction about same. I have the intellectual capacity to do so, I suppose.

The problem is, as you have determined by now, I don’t give a rat’s ass about somebody coming of age. It is without a doubt some of the most boring fodder for storytelling in the entirety of the human experience.

As I mentioned above, not all stories labeled as coming of age must deal with these topics. I stand by my assertion that a majority do to at least a degree. Yet even the works that don’t even touch on (no pun intended) a sexual awakening as it were, delve into topics that overwhelming conform to a narrow definition of what it is to pass from childhood into adulthood, particularly in the United States.

I went through none of it, and am happy to keep it both off my bookshelves and out of my catalog.